“You rarely have time for everything in this life, so you need to make choices. And hopefully your choices can come from a deep sense of who you are.” —Fred Rogers

THIS PAST SUMMER, it was one of those mornings—I was feeling a little groggy, my mind and heart a bit worn-out from the everyday grind of a morning routine with a rambunctious toddler and an overflowing inbox. I had not yet awoken my daughter, and as I usually do, I sat down to browse the various news outlets while I crunched on my cereal. I stumbled across a long-form essay in The Atlantic about a mother and her son after his severe brain injury; I am not sure what compelled me to click on an article seemingly so far out of my intellectual comfort zone. But I did, and when I finished, I cried: I just broke down, sobbing while my wife—who now joined me downstairs with my daughter—rushed to my side, as if something was wrong. My tears continued in her arms. I was not even sure why I was crying, but for some reason I was, unexpectedly thrust into a deep reflection about life and mortality—and love—at 7:15am on a weekday morning. After I regained composure, I jumped to go play with my daughter: to kiss her little cheeks, squeeze her tightly, admire her smile. The banality of the morning immediately faded and I admittedly felt a wave of guilt flow through me for even feeling the tiniest bit of “blah” upon waking.

My family and friends know that I am of the sentimental type. But for some reason, this beautiful essay made me feel in ways I had not in a while. There is too much weightiness and beauty in the essay for me to accurately synthesize it here—it is stunning writing—but in short, it is a very sad story of a teenage boy in the 1970s who was struck by a car, survived, but only in what we refer to (albeit problematically as I learned) in a vegetative state, with minimal consciousness and little to no use of his body. It is indeed a tragic story, filled with rich discussion of neuroscience and brain injuries, all topics that I am (fortunately) not very knowledgeable about. Yet, the story wasn’t really about tragedy at all, actually. It was a story about unconditional love: a mother’s love and a brother’s love and a re-imagination of love itself.

Most of all, it was a breathtaking story about a few people’s profound capacity to love.

The rest of that morning, I did not know what to think, or what to feel, or how to make sense of any of what I read. But eventually as I settled myself into the rigidity of my daily routine, I realized that my response to reading this article was the most “human” I had felt in a long time—the full rush of emotions of sadness, grief, gratitude, kindness, and love besieged my heart and my mind. But, above all, for the rest of the day, I could not stop thinking about this one particular concept emphasized by the mother in that essay: her extraordinary capacity to love.

*****

THIS LAST YEAR AND A HALF has been wild and challenging, if not also beautiful: my daughter is now over two and half years old, and she is a supremely happy little girl with a smile and laughter that brings me unbridled joy, even amidst the exhaustion and new challenges of the “terrible twos.” Still, our lives have settled into a routine that two years ago would have seemed foreign amidst the chaos of a newborn. This routine—even as I still search for my own equilibrium of happiness—has allowed me to accomplish long-awaited goals and seek out new ones. My book, Strength through Diversity, which took me well over a decade to research, write, and then publish, is finally available to the world as of last January. This dream achieved and prodigious project finally behind me, plus being home—a lot!—taking care of my toddler, I have been able to think a bit more on my personal growth. Those who knows me are familiar with my physical health and wellness goals, where I’ve been challenging myself in the gym more than in years past. I’ve been reading consistently again, challenging myself intellectually as well, trying to keep my mind sharp and elastic. More than ever, I’ve been reading and listening to ideas that challenge my politics and preconceptions, the things I thought I was right about or to seek better understanding of our world that seems to be aflame. It has been stimulating weaving new exercise workouts with new books and different voices. So, while I worked on my physical and intellectual growth this year, until the article in The Atlantic, I had not thought about my emotional growth much at all. Have I expanded my own capacity to love? Can I expand it even more?

Our chosen home decor right above our living room mantle in our home.

I actually thought about this same question, if more rudimentarily, a few years ago when my wife was pregnant. We thought we had always wanted kids, but at the same time, we were not 100% sure, either. Our lives already felt so full in our partnership and I loved her so much—loving my wife gave me all the “purpose” and joy I could ever imagine. So, when she did become pregnant, I had this constant worry: could I find more room in my heart to love another being just as much? The answer, of course, was “yes,” and while it seems silly in retrospect, the paradox is not: where you feel your life is full and you do not need to seek out more love, but then when you feel more and you grasp it—you realize you are better for it. This doesn’t have to be a child; it can be a friend or coworker or a neighbor, or maybe even a stranger. And all of this doesn’t mean you stop loving those who you loved before, but you just somehow find more room in your heart. Your heart grows like one’s muscle or mind. This love makes us fuller, it makes us more ambitious, it makes us keep striving to be better for this additional human who is now part of our orbit.

Of course, this is not the first time I am posturing about love more generally—I know it’s not yours either. Nearly a decade ago, I wrote about the importance of love in maintaining a connected society; no amount of laws (or law enforcement) can exist without a belief in a creating a social fabric, underwritten with empathy for others. But I have realized in the decade since that in order to be “driven by love” as I wrote then, we need to do two things: one, define it and then act on it in much broader terms that we often do; and two—the topic of this essay—tangibly grow our own capacity to love so that we feel its power, its radiance, its ability to indeed make us better humans.

What does a more holistic definition of love “look” like? “When we think of love, we think of romance and happily-ever-after fairy tales,” writes Suleika Jaouad. In her story about a friend’s illness, she explains how love is “the radical power of seeing, understanding, and showing up for another human.” She quotes a famous British novelist who further writes that the word love “is fatefully associated with romance and sentimentality that we overlook its critical role in helping us to keep faith with life at times of overwhelming psychological confusion and sorrow.” Or, more simply, as one of my remarkable best friends told me, “you love differently” in different ways to different people—and in different moments.

It is through this definition of love that we must grow our capacity to obtain more of it, not just in our relationships with those we already “know” we love like our friends and family, but in our everyday interactions with strangers and the world. What are the stories, the movies, the music—and the people curating these forms of media—that challenge us to expand our capacity to love? Who can we can listen to or read from or inquire about that challenge us to love people and topics, not criticize or even hate, that we do not fully understand? How do we create little moments in our lives that can create larger shifts that make our hearts truly smile and make us feel in ways that bring out our shared humanity?

A quick selfie before I walked into the theater with my wife to view Interstellar, this time with a daughter of my own.

I think about when I saw Interstellar for its 10th anniversary in 10mm IMAX with my wife last fall (my absolute favorite movie of all time). I was teary-eyed nearly the whole movie thinking about a father’s love for his daughter and the concept of time passing. As The Bulwark wrote regarding its re-release: “Interstellar is a movie that posits love being a force like gravity that can transcend time and space and dimensions to save humanity from its own destruction... I have come to love the film unreservedly for the way it deals with family and parents and children and love and every time I watch it now I walk away a weeping mess.” I did that night, too, and I fully agree—and I want more of that feeling, all the time.

One of the best things about being a parent is watching your child learn to love and understand its eternal power. My daughter’s capacity to love is endless—it has no boundaries. It is beyond beautiful to see how she grows her capacity to love literally every day: her “friends” (i.e., stuffed animals gifted to her) who she snuggles with wonder, her family who she endearingly will call out for with joy and point to her chest when they say “love you,” strangers she meets who she blows kisses, and even herself when she feels joy and smiles when she accomplishes a task. It’s all absolutely magical. Love is so deeply central to her young existence in this world.

A quote that perfectly encapsulates my grandpa and my grandma, who carries on his (and continues her own) legacy.

But, notably, examples of the capacity to love are not exclusive to a parent and child. I am reminded of my grandfather and his longtime involvement with the Meals on Wheels program (which has been in the news due to funding cuts affecting seniors all over the country). Meals on Wheels is a federal program—part of the Older Americans Act passed during the Great Society programs of the ‘60s—that provides critical food service to low-income senior citizens who are ill or unable to prepare food themselves. Volunteers deliver food but just as importantly provide wellness checks and social connection to these seniors who are isolated at home. My grandma tells the story of how, while working as a secretary at her synagogue—which helped distribute food in her neighborhood—asked a family member of one of the recipients how the deliveries have been going. The family member replied that it was going fine, but the woman receiving the meals wanted to request that it always be the “tall, handsome man” deliver the food, as opposed to other volunteers. (This handsome man was her husband, of course—my grandpa—but the person speaking did not know that!) When my grandma asked why him, the person said: “Because he doesn’t just deliver the food, but he comes in, puts the food in the refrigerator, and stays to talk and engage in conversation.” She went on and on—according to my grandma—about how this man was so friendly and generous with his time. This elderly woman felt loved in that moment, and it really made a difference in relieving her constant loneliness. Despite tremendous hardship throughout his entire life, my grandpa’s capacity to love was second to none: he thrived on helping others and saw the humanity in every single person. He loved life, in part because he loved people and their stories.

What about the role of schools in growing students’ capacity to love? As a professor of education who teaches about 1,000 students a year, this is a question I think about every single day. While higher education has its many issues, at a time where universities are under unprecedented attacks, I witness every day the way in which students learn real cognitive skills of how to assess information, think critically across different viewpoints, craft arguments, and collaborate with others; I also witness how it is “good,” in my estimation, that young people are exposed to new ideas, one course, one professor, one reading, one classmate at a time across disciplines and fields (even if we could use more ideas). But, part of what happens in college is that—in this process of learning and stretching our intellectual capacities—is that, if we do it right (and we don’t always, to be sure), we also build empathy, learn what it means to extend grace to others, and, yes, ultimately, grow our capacity to love. In my classes, this is central to what we do: despite commentary otherwise, research convincingly shows that, on average, more empathetic people experience more professional success and greater well-being.

Other examples about growing one’s capacity to love abound at the K-12 level. One just flat out super cool program is The American Exchange Project, a student exchange program not based on some far-off country, but within the United States. “Urban and rural teens swap hometowns and are shocked by what they learn about each other,” reads the headline about this program in the Los Angeles Times. I love this program so much because it directly pushes in kids’ natural curiosity, wonder, and discovery to the forefront, and pushes out stereotypes and misconceptions that they’ve grown up with and internalized (often through media). It expands kids’ capacity to love others—to form meaningful bonds—across racial, religious, ethnic, socioeconomic, political, and geographic divides within our diverse country. As I write in my book, I think we have to be curious about each other, but too often, our innate curiosity that we all possess is pushed aside: we do not even attempt to grow our capacity to love. Our “hearts” become static, and outside our immediate circle of family and friends, we then begin to perversely find entertainment in the suffering or demeaning of others. We know scientifically that we have to expand our mind to keep it cogent, and that we have to keep challenging our muscles to keep them strong. But I have come to believe that our “hearts”—our consciousness as humans, perhaps our souls for those who are more spiritual—also must be exercised, too. It, too, can grow and contract like our minds and our muscles.

*****

SO, WHEN DID WE stop trying to expand our capacity to love—stop listening and reading and watching things that would expand this capacity, as opposed to restricting it or even hoarding it for ourselves? And why? Of the dozen or so books that I’ve read since January, one of the most provocative (even if a bit dry!) was a book called The Upswing by renowned political scientist Robert Putnam. Putnam and his co-author argue through a litany of research how America has moved from a period of selfish pursuit in the Gilded Age of the 1890s to common purpose in the mid-1900s back to selfishness in recent decades, or, as he puts it, from “I” to “We” back to “I.” And, as a result, we are the most economically stratified, politically polarized, socially fragmented, and culturally divided since the Gilded Age. This lack of cohesion and care for our fellow citizen, among many things, foregrounds the inability to solve major problems. I am further reminded of my graduate school advisor and her beautiful tribute to her dad after his passing, in which despite his politics differing from hers, he understood that we all depend on others in this fragile life.

And so here we are in the present—and I am struck how arguing for growing one’s capacity to love seems so antithetical to the news and to the words of (seemingly) so many popular commentators and often our representatives. With the avalanche of information at our fingertips, politics has become pop culture and entertainment: it’s ubiquitous. While I hesitate to wade into the fraught political arena, it’s hard not to do so when our all-consuming political culture has become one of cruelty, not love. Certainly, politicians have always decried their opponents with the most vile insults dating back to our founding—they are “in the arena,” as Teddy Roosevelt once proclaimed—but attacks on common folk, on each other, by each other, just feels different. There has been a sharp attack on empathy in our politics, where both cruelty and even the theater of cruelty is applauded, even desired. It seems like the more suffering that a person can impart on those “we” (those in positions of power) are not “supposed” to like—the immigrant mother in fear of being separated from her family just like her husband or the trans student being bullied into suicide or the poor rural grandmother in Appalachia unable to put food on the table—the more notoriety that person gains. Unfortunately, to denigrate a person or group is much easier—and certainly more profitable, whether through dollars or influence—than the internal work of growing your capacity to love. Because in the “attention economy,” our “likes,” our listening, our scrolling is monetized, and nothing grabs attention like outrage, conspiracy, and spectacle, whether it’s true or not. Love, on the other hand, does not have that same affectation.

To be clear, this is not at all about policy, even if and when I sharply disagree. As a historian who has studied public policy, I am not naïve to believe that love can always be the guiding light in our policy-making. There is a myriad of practical, legal, financial, ethical, and even safety considerations within every policy decision. Life is rarely fair, and we must maturely balance our empathy with what is possible. The world is exceedingly complex, and too often we flatten these issues—just like we flatten the depth and complexity of every person. After all, more than 90 million people did not vote in the last presidential election: more votes than either candidate received, suggesting, at least to some degree, just how many Americans did not find themselves reflected in either option (many of whom undoubtedly share these values of decency and care). I think we all can, from every “side,” do better in extending much more grace and less judgement within current policy disagreements. (That includes me, too, as my goal next year is also to be more open-minded and recognize there is more uncertainty than we want to admit!) Instead, my disheartenment is about the entertainment we gain from seeing people, our fellow Americans and humans, suffer or be demeaned. Because even if you support a policy, for any number of personal beliefs or practical reasons, that might cause harm to some group, you advocate for it with a heavy heart—not with glee and celebration.

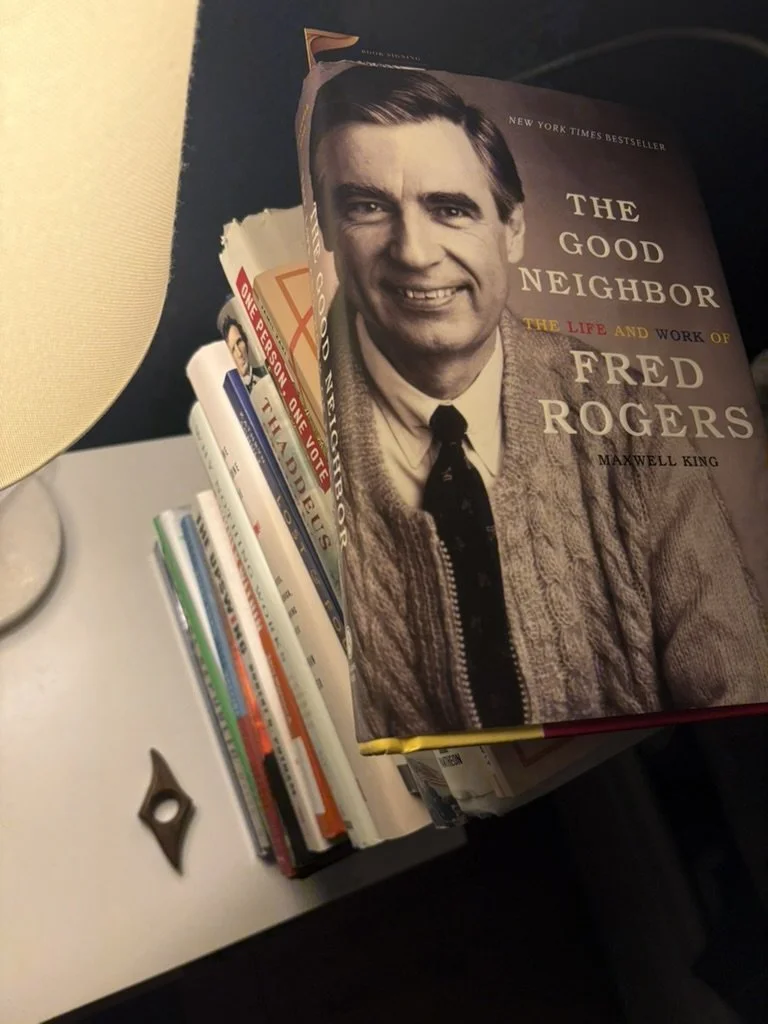

My nightstand stack of books I read this year. (My daughter is obsessed with Misters Rogers’ music, and so I decided to pick up a biography of his life.) As you can see, this book is on my mind!

In short, our political culture has become about grievance, hate, and fear: of the opposite of “love thy neighbor” and recognizing our fellow American as worthy not just of common dignity, but the love of anyone, whether a spouse, parent, friend, or representative. And because our politics (and our partisanship) have become so central to our everyday existence in the “rage economy,” we then internalize and normalize these behaviors. Quite simply, I believe everyone deserves to have love and to be loved. I don’t want to hurt anyone, I want to learn to love everyone—to grow my capacity to love—particularly those who I do not understand. Of course, there is a “moral line” that I have (and I think we all should have) about treating everyone with decency—a line, that at least as I believe, is crossed by our leaders and commentators that veers into racism, antisemitism, misogyny, homophobia, and so much more. How, or if we even should, bridge divides with those so clearly (to me) over our moral lines, who dehumanize others, is a question I struggle with, and do not have an answer to. What I will say is that, unlike hate, to love another person takes courage and bravery; it takes inner strength and fortitude. All of this is why love is among our highest virtues: we strive for it, even if we cannot always perfectly attain it. Of all the books I read this year, my favorite is my current one—a surprisingly moving and thought-provoking biography of Mister Rogers, who understood that the most important affirmation we can teach children is to say “I love you” to others and, most of all, to themselves.

Ultimately, we’ve all been conditioned to see politics, and well, other people different than us, as zero-sum: the suffering of another leads to our personal benefit. But is this what we want our politics to be—both our “political” politics as well as our personal ethos? Is politics just the “organization of our hatreds,” as Henry Adams once exclaimed? Of summoning fear and resentment? Or, is politics about bridging divides and bringing people together? About solving problems and helping others pursue a better life? As the popular (if at times controversial) New York Times podcaster Ezra Klein further explained, if it’s the former—a way to build a dislike of groups that I am not a part of—then I (too) have no interest in making that part of my civic or social life. I don’t want to actively push away the most essential component of life—my capacity to love—for any reason.

To be sure, people across our diverse country have a range of personal beliefs, which are deeply shaped by each person’s unique experiences. I grew up in Missouri, lived in New York, and reside now in California. I spent time in South Africa, and read everything from the New York Times to The Atlantic to the Wall Street Journal, to even the City Journal. I teach over a thousand students each year from all walks of life, backgrounds, and identities, from urban, suburban, and rural areas. But as I’ve grown as a professor, I realize that I find so much fulfillment and richness in learning my students’ unique stories. This goes hand-in-hand with my fascination in trying to challenge my worldview, learning different ideas from people and from spaces that present the world differently than I have come to understand it. Social media can distort our frames of reference: we assume that the way we see the world, and the events that happen (and events that do happen but are not presented to us by the algorithm or the certain outlets we follow) are the ways that everyone sees it. But that is just not the case and it’s really, really, really hard to escape the algorithms that entrap us all. But, I believe that if we are more purposeful about growing our capacity to love, we can escape that trap—and, I believe, reap the benefits in return.

*****

MY FAVORITE PART OF life is the many textures and variables of it—the waves of emotion that make us feel alive, the feelings of genuine joy, whether through friendship or family or simply self-satisfaction of “duty” after a long day. The author Katheryn Shulz makes the point that there is a difference between happiness and fun; too often, we only seek out moments of fun, but those moments of fun are always fleeting. They do not last. They are finite: a night out with friends, engaging in our favorite hobby, watching a comedic YouTube clip. These can all lead to important (and necessary) moments of fun—and we should strive for more laughter and this type of fun that I could really use more of!—but, at the same time, it is impossible to fill every moment of every day with “fun.” Days are just too long (even if the years are absolutely way too short). Instead, if we can find contentment in duty, satisfaction in the “little moments” that are laced with love as I wrote almost a decade and a half ago, our hearts and souls can become closer to feeling satiated.

I can relate to this idea a few weeks ago. It was late on a Monday night. I was still exhausted from the previous week. Yet, there I was, prepping food for my daughter for the week ahead, listening to music, hot food on the oven and stove, the glass containers queued up in a perfect line on the counter. When I put it all in the fridge, I felt fulfilled in my heart, because it was my duty as a parent—as a father—to make sure my beautiful daughter, whom I love more than I could ever express, had food for the week. I found so much joy in that (and great gratitude that I have the resources to provide these meals, too). A rush of deep satisfaction overcame me, perhaps a quick jolt of happiness, too, even if what I was doing at that moment of exhaustion definitely was not fun. If my capacity to love was a meter, it would have ticked up the tiniest notch.

Coming full circle, it’s not always fun to grow one’s capacity to love; nor is it always easy (or, admittedly, even always possible). I readily confess to not always taking my own advice: seeking the confirmation of my biases (which we all have) instead of my intellectual growth, mistaking my contentment for what actually was (and often still is) my stubbornness, and falling prey to stereotypes and the flat portrayals of strangers and groups. I think about my inspiring friend who reminds me—teaches me, really—that hate is too strong a word, and that we can disagree while staying in the spirit of love. I strive to be better, to follow her important example. Again, all of this is hard and all of it requires a humility that the enigmatic emotion of love promotes. Because at the end of the day, I do believe that growing our capacity to love can make us feel more fulfilled as humans. Our spirits feel healthier, our lives more enriched, our relationships deeper, and our souls more gratified. Love is what we live for. Shouldn’t we try to seek as much of it as we can?

When I think about what 2026 will entail, I am reminded of my need to greatly enlarge my capacity to love in unprecedented ways: my wife and I will welcome our second child in 2026, a son, who will require of me more love than I have ever given in this life so far. (Fittingly, he will be named after my aforementioned grandpa.) It won’t be easy, and yes, at times, it won’t be fun—and yes, referring back to my earlier definitions of love, my love for my son will not only be hugs and kisses, but “showing up” for this tiny human and keeping the faith in times of what I know will be “overwhelming psychological confusion.” But I’ll also do my best to model to my son and daughter what it looks like to love others, even—and especially—when it’s hard. At the end of the day, love is the universe’s most precious gift in the larger gift of life. I plan on trying to open that gift every possible moment I can, in my all interactions and all my endeavors, for as long as I can. That is my noble goal for the upcoming year. I hope it’ll be yours, too.